Concrétiser la gouvernance partenariale grâce à l’actionnariat salarié : perspectives de Tim Garbinsky du NCEO

November 10, 2025

Lorsque Tim Garbinsky accepta un poste de commis à Madison, dans le Wisconsin, il ne s’attendait pas à ce que cela oriente le cours de sa carrière. Il s’agissait d’un emploi modeste dans une pharmacie locale. Toutefois, ce qui fit une différence, c’était que l’entreprise appartenait aux employé.e.s. « Ce n’était pas comme travailler dans votre magasin Walgreens ordinaire [équivalent de Pharmaprix] », s’est-il souvenu. « Il y avait un véritable sentiment d’adhésion. Les commis, les magasinières, les magasiniers et les pharmacien.ne.s étaient davantage sur un pied d’égalité. » Ce sentiment de dignité et de responsabilisation partagées l’a immédiatement frappé, non parce que c’était une politique écrite, mais car il s’agissait d’une véritable culture, du type de celles qui façonnent les interactions quotidiennes. Cette expérience l’a convaincu du pouvoir de la propriété pour changer les vies.

Aujourd’hui directeur des communications au National Center for Employee Ownership (NCEO, centre national pour l’actionariat salarié) [en anglais], Tim explique que la propriété n’est pas qu’une question d’économie. Il s’agit aussi de la base de la communauté et de la stabilité sociale. « J’en suis arrivé à la conclusion que l’un des éléments essentiels à la prospérité et à la cohésion sociale qui fait défaut est l’accès plus large à la propriété : la propriété résidentielle, la propriété communautaire, la propriété commerciale et l’actionnariat salarié », a-t-il affirmé. « Il s’agit d’une pièce cruciale du casse-tête qui entraîne une réaction en chaîne dans l’ensemble de la société. Cela semble peu perspicace de parler d’enjeux comme la violence ou la criminalité sans reconnaître leur cause profonde : les gens ont des besoins non comblés. La propriété n’est pas la seule solution, mais elle constitue une partie essentielle de la réponse, quelle qu’elle soit. »

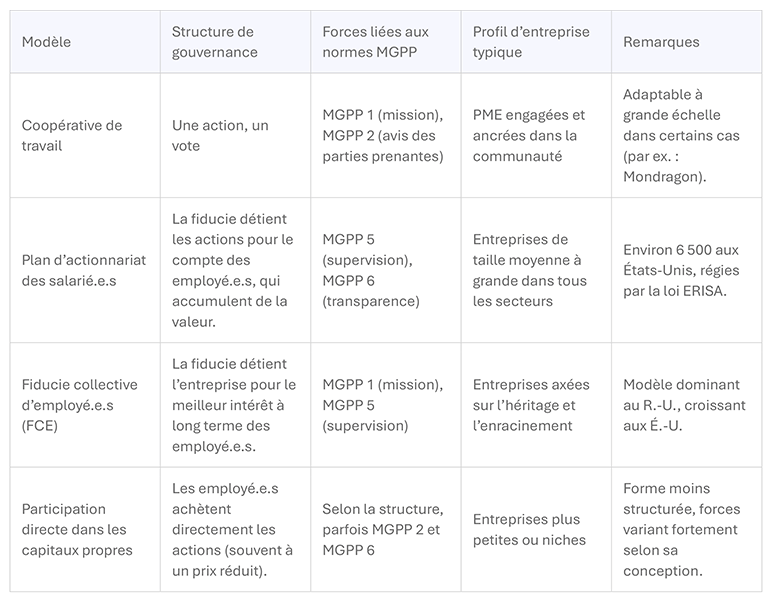

Le nouveau domaine d’impact de la mission et de la gouvernance des parties prenantes (MGPP pour Purpose and Stakeholder Governance) [en anglais] du B Lab traite du même défi sous-jacent que Tim a abordé : comment créer des entreprises dans lesquelles la prospérité est partagée et les voix des parties prenantes exercent une véritable influence. L’actionnariat salarié offre l’une des avenues les plus claires pour mettre ces normes en pratique. Des modèles comme les coopératives de travail, les plans d’actionnariat des salarié.e.s (ESOP), les fiducies collectives d’employé.e.s (FCE) et la participation directe dans les capitaux propres offrent des mécanismes pour distribuer la richesse, mais aussi des cadres pour intégrer la dignité, la responsabilisation et la voix du personnel directement dans la gouvernance.

Le lien entre les normes MGPP et l’actionnariat salarié

Les normes pour le domaine de la mission et de la gouvernance des parties prenantes ont été créées en vue de faire passer les entreprises du schéma de la primauté des actionnaires (l’idée qu’une société existe seulement afin de maximiser les bénéfices de ses propriétaires) à un modèle dans le cadre duquel la mission à long terme et la responsabilisation à l’égard de toutes les parties prenantes guident les décisions. Plutôt que de demander aux entreprises d’adhérer à des valeurs nobles, les normes définissent un cadre de gouvernance concret qui donne une place à part entière à la voix des parties prenantes dans le fonctionnement réel d’une entreprise.

Les six exigences du domaine couvrent les parties essentielles de la gouvernance responsable :

- MGPP 1. Mission : toutes les entreprises doivent définir une mission positive dont la portée s’étend au-delà de la rentabilité financière et qui ancre sa stratégie.

- MGPP 2. Avis des parties prenantes : les entreprises doivent avoir mis en place des processus clairs permettant de prendre en compte les points de vue des employé.e.s, des client.e.s et des communautés, ainsi que l’environnement, dans les décisions essentielles.

- MGPP 3. Mécanismes de réclamation : les parties prenantes doivent disposer de moyens sûrs et accessibles pour soulever des préoccupations et les entreprises doivent prendre la responsabilité de les résoudre.

- MGPP 4. Communication responsable : les entreprises doivent faire preuve d’honnêteté et de pondération dans leurs discours sur leur impact social et environnemental.

- MGPP 5. Supervision : la direction des entreprises doit intégrer la mission et la gouvernance partenariale à l’ordre du jour des conseils d’administration et dans les responsabilités des dirigeant.e.s.

- MGPP 6. Transparence : les entreprises doivent communiquer publiquement, sur une base régulière, le rendement de leur impact. Les attentes de cette norme sont plus élevées pour les entreprises plus grandes ou plus complexes.

Ce cadre s’adapte au contexte : une jeune entreprise qui compte 15 employé.e.s n’est pas tenue de répondre aux mêmes attentes en matière de gouvernance qu’une multinationale. Les petites entreprises peuvent respecter les normes en mettant en place des boucles de rétroaction simples ou un processus de réclamation élémentaire tandis que les grandes sociétés doivent démontrer une supervision à l’échelle du conseil d’administration, une responsabilisation de la haute direction et des processus de déclarations publiques solides.

Ce qui distingue les normes MGPP, c’est qu’elles ne prescrivent pas une forme de gouvernance unique. À la place, elles créent de l’espace afin de permettre aux entreprises de choisir les structures qui conviennent à leur taille, à leur culture et à leur secteur d’activités tout en garantissant que la mission et la responsabilisation à l’égard des parties prenantes ne sont pas négociables.

C’est dans ce cadre que l’actionnariat salarié entre en jeu. En donnant aux collaboratrices et aux collaborateurs une participation financière et une voix dans la gouvernance, les structures d’actionnariat, comme les coopératives, les plans d’actionnariat des salarié.e.s, les fiducies et les programmes de participation directe fournissent des mécanismes intégrés permettant une prise de décision inclusive, la transparence et la responsabilisation à long terme. En pratique, elles offrent aux entreprises une voie toute tracée pour répondre à de nombreuses exigences ancrées dans le cadre des normes MGPP.

WinCo Foods, une chaîne d’épiceries basée à Boise, se classe en haut de la liste des « 100 entreprises appartenant aux employé.e.s » de NCEO [en anglais].

Photo : Zoshua Colah

Les formes d’actionnariat salarié (et comment elles font avancer la gouvernance partenariale)

L’actionnariat salarié n’est pas une formule unique convenant à tout le monde. Comme Tim l’a formulé : « Je considère l’actionnariat salarié comme une trousse à outils. Coopératives de travail, plans d’actionnariat des salarié.e.s, fiducies collectives d’employé.e.s, programmes de participation directe : chacune de ces structures apporte des points forts différents à la table des discussions. Aucun modèle n’est parfait, mais, parmi ces structures, presque toutes les entreprises peuvent généralement en trouver une qui leur convient. » Tandis que tous les modèles adoptent une approche différente pour distribuer les parts de propriété et les voix, ils ont tous en commun la capacité de faire passer la gouvernance partenariale du stade de politiques sur papier à l’état de véritable culture.

Plans d’actionnariat des salarié.e.s (ESOP aux États-Unis)

Les plans d’actionnariat des salarié.e.s sont la forme la plus courante d’actionnariat salarié aux États-Unis. En effet, environ 6 500 entreprises ont adopté cette structure [en anglais]. Au lieu de donner à chaque collaboratrice et collaborateur un droit de vote direct, les plans d’actionnariat des salarié.e.s créent une fiducie qui détient les actions de l’entreprise pour le compte des employé.e.s. Les actions sont allouées à des comptes individuels qui prennent de la valeur au fil du temps, à mesure que l’entreprise réalise des bénéfices, et les employé.e.s ne paient rien de leur poche pour les acquérir. « Au cours de mes dix années de service, je n’ai jamais connu un.e employé.e qui a dû les acheter personnellement », a remarqué Tim. « Il s’agit véritablement d’un avantage acquis grâce au travail au fil du temps. »

Cette structure fait des plans d’actionnariat des salarié.e.s des outils puissants pour sécuriser la retraite. Tim se souvient d’avoir interrogé dans le cadre d’un entretien un ouvrier de la fabrication électrique qui avait pris sa retraite deux ans plus tôt grâce au solde de son plan d’actionnariat des salarié.e.s. « Vous entendez des histoires de commis d’épicerie ayant à 45 ans des comptes de retraite contenant un million de dollars. Dans un pays où les prestations de retraite ont disparu et où les cotisations aux plans d’épargne 401k dépendent des contributions des employé.e.s, qui sont puisées dans leur salaire, les plans d’actionnariat des salarié.e.s comblent une lacune. Ils permettent de garantir que les gens ne doivent pas travailler jusqu’à 80 ans. »

Du point de vue de la gouvernance, les plans d’actionnariat des salarié.e.s se rattachent plus directement aux normes MGPP 5 (supervision) et MGPP 6 (transparence). En vertu de la loi ERISA (loi américaine sur la sécurité du revenu de retraite des employé.e.s), l’organisme fiduciaire est légalement tenu d’agir dans le meilleur intérêt des employé.e.s-propriétaires. Le département du Travail des États-Unis peut faire respecter cette obligation, notamment en enquêtant sur les cas de violation, en intentant des poursuites judiciaires et en accordant des indemnités aux employé.e.s participant aux plans. En pratique, ceci signifie que la responsabilisation n’est pas seulement culturelle, mais aussi légale. « Dans une entreprise conventionnelle, les propriétaires peuvent vendre si le prix semble juste. Dans le cadre d’un plan d’actionnariat des salarié.e.s, les fiduciaires doivent se demander si la vente, au moment donné, est vraiment dans l’intérêt à long terme des employé.e.s », a expliqué Tim.

De plus, la transparence est intégrée dans la structure. En vertu de la loi, les entreprises dotées d’un plan d’actionnariat des salarié.e.s doivent communiquer les informations détaillées du plan, l’évaluation annuelle des actions et d’autres divulgations, des renseignements qui ne seraient jamais transmis aux employé.e.s dans une entreprise conventionnelle. Les collaboratrices et les collaborateurs ont souvent l’occasion de voter sur des questions d’ordre global, comme une vente potentielle, permettant d’assurer que leurs voix sont prises en compte aux moments décisifs.

La force des plans d’actionnariat des salarié.e.s repose non seulement dans la richesse qu’ils aident à constituer, mais aussi dans ses garde-fous qui maintiennent les entreprises responsables. Les entreprises dotées de ces plans créent davantage de travail [en anglais], connaissent moins de défauts de paiement de prêts et sont considérablement plus susceptibles de survivre aux ralentissements économiques que leurs pairs détenus de manière conventionnelle. Prises conjointement, ces forces font des plans d’actionnariat des salarié.e.s un outil de création de richesse et un modèle résilient de gouvernance.

Coopératives de travail

Les coopératives de travail sont la forme d’actionnariat salarié la plus ancienne et la plus intuitive. Elles sont fondées sur le principe « une part, un vote », donnant à chaque employé.e une voix égale dans les décisions importantes. Pour de nombreuses personnes, il s’agit de la forme d’expression la plus claire de gouvernance démocratique.

Aux États-Unis, les coopératives sont souvent associées à l’image de petites entreprises communautaires, tels que des épiceries, des cafés ou des librairies. Toutefois, Tim repousse l’idée que cette structure ne peut pas être instaurée à plus grande échelle : « L’une des plus grandes entreprises détenues par les employé.e.s au monde, Mondragon, en Espagne, est une fédération d’entreprises appartenant aux salarié.e.s dans laquelle des dizaines de milliers de personnes, voire près d’une centaine de milliers, sont impliquées. Ceci prouve que les coopératives ne sont pas seulement des petits magasins familiaux. Elles peuvent être des entreprises grandes et complexes. »

Dans le cadre de ses recherches, le NCEO a recensé plus de 750 coopératives de travail aux États-Unis [en anglais], dans un éventail de secteurs d’activités, allant des services alimentaires aux soins de santé, en passant par la fabrication, les technologies et la conception. Sur le plan structurel, chaque employé.e. achète une part qui lui confère une participation dans les capitaux propres et un droit de vote pour l’élection des membres du conseil d’administration. Ce conseil supervise la stratégie et recrute des gestionnaires professionnel.le.s ou délègue les activités quotidiennes. La gouvernance demeure donc démocratique sans devenir pesante.

Étant donné que les coopératives intègrent les avantages pour le personnel et la communauté dans leurs missions, cette forme d’actionnariat fait écho à la norme MGPP 1 (mission), qui oblige les entreprises à définir une mission positive dont la portée s’étend au-delà de la rentabilité financière. Elle est aussi plus directement liée à la norme MGPP 2 (avis des parties prenantes). « L’entreprise doit être attentive à ce que les employé.e.s souhaitent, car il s’agit des personnes qui la contrôlent », a expliqué Tim. La gestion quotidienne est menée par des conseils d’administration élus ou des gestionnaires professionel.le.s, mais la direction stratégique demeure dans les mains des employé.e.s-propriétaires. Tim s’est empressé d’ajouter que les coopératives ne sont pas des structures chaotiques : « Les gens pensent parfois que tout le monde est impliqué dans toutes les décisions ou qu’il est possible de congédier sa ou son collègue. Les choses ne se passent pas comme cela. Les coopératives de travail fonctionnent selon des règles et des pratiques exemplaires bien établies. »

Au contraire des plans d’actionnariat des salarié.e.s, les parts de coopératives ne sont pas conçues comme des avantages de retraite : les employé.e.s peuvent toujours contribuer à des plans d’épargne 401k, mais leur part représente plus une voix et une responsabilité qu’une source de création de richesse sur le long terme.

Fiducies collectives d’employé.e.s (FCE ou EOT aux États-Unis)

Les fiducies collectives d’employé.e.s sont une structure relativement nouvelle aux États-Unis. Toutefois, il s’agit de la principale forme d’actionnariat salarié au Royaume-Uni. Dans le cadre de ce modèle, l’entreprise est détenue par une fiducie qui est légalement tenue d’agir dans le meilleur intérêt des employé.e.s. Contrairement aux coopératives ou aux plans d’actionnariat des salarié.e.s, les parts ne sont pas allouées individuellement. C’est la fiducie qui détient l’entreprise et les employé.e.s reçoivent généralement une quote-part des bénéfices au moyen de régimes d’intéressement et de retraite.

Étant donné que les documents constitutifs de la fiducie peuvent être rédigés en donnant une place centrale au bien-être des employé.e.s, les FCE sont souvent la structure qui répond le mieux aux exigences des normes MGPP 1 (mission) et MGPP 5 (supervision). « L’idée est que si vous souhaitez dire non à une vente, vous le pouvez », a clarifié Tim. « La fiducie peut décider de maintenir l’entreprise ancrée dans la communauté et de préserver les emplois, parce que sa mission ne consiste pas seulement à maximiser les bénéfices des actionnaires, mais aussi à veiller au bien-être des employé.e.s. »

Aux États-Unis, les fiducies collectives d’employé.e.s ne sont pas couvertes par la loi ERISA comme les plans d’actionnariat des salariés, ce qui signifie qu’elles ne bénéficient pas du même type de cadre réglementaire. Toutefois, cela leur permet aussi d’éviter une partie de la rigidité associée. Cette flexibilité les rend attrayantes pour les petites entreprises qui recherchent une manière abordable d’intégrer les priorités des parties prenantes dans la gouvernance. Même s’il n’existe qu’environ 60 fiducies collectives aujourd’hui aux États-Unis [en anglais], elles gagnent en popularité alors que davantage de fondatrices et de fondateurs recherchent des plans de succession qui entérinent l’intendance à long terme plutôt que la valeur de sortie à court terme.

Participation directe dans les capitaux propres

Le modèle d’actionnariat salarié le plus simple est la participation directe dans les capitaux propres. Dans le cadre de cette structure, les employé.e.s achètent directement des parts, parfois à un prix réduit ou au fil du temps. Cette approche est très flexible. Certaines entreprises la combinent à un fonds réservé à un régime d’intéressement ou octroient aux employé.e.s un nombre d’actions égal au nombre d’actions achetées. Dans certains cas, les vendeuses et les vendeurs rendent l’actionnariat salarié possible en proposant des prix réduits, des prêts financés par l’entité venderesse ou l’option d’utiliser les primes pour acheter des parts.

Parce que ce modèle d’actionnariat salarié repose sur la capacité et la volonté des employé.e.s à investir, la participation directe dans les capitaux propres fonctionne souvent le mieux dans les petites entreprises ou dans le cadre d’un plan de succession graduel. Elle peut aussi prendre la forme d’un plan d’avantages sur capitaux propres, comme des options de souscription d’actions, des régimes d’achat de titres ou des plans d’octroi d’actions assujetties à des restrictions. Cette forme permet rarement de transférer la majorité des capitaux propres d’une entreprise, mais elle contribue à renforcer l’engagement et récompense les années de service.

La participation directe dans les capitaux propres peut faire avancer les normes MGPP 2 (voix des parties prenantes) et MGPP 6 (transparence). Cependant, son efficacité dépend fortement de la manière dont les actions sont réparties et si des droits de gouvernance y sont associés. Sans ces éléments, la participation risque de devenir plus symbolique que structurelle.

Comme Tim l’a souligné, aucun modèle ne répond à toutes les exigences des normes MGPP seul. Les coopératives de travail sont une excellente structure pour ce qui est de la gouvernance démocratique, les plans d’actionnariat des salarié.e.s pour la création de richesse et la responsabilisation, les fiducies collectives pour la mission et l’intendance et la participation directe dans les capitaux propres pour la flexibilité. « Il n’existe pas de solution miracle », a-t-il commenté. « Toutefois, chaque modèle répond au minimum à quelques exigences des normes, souvent à plusieurs d’entre elles, d’une manière significative. »

Le résultat prend la forme d’une trousse à outils dans laquelle les entreprises de toutes tailles et de tous secteurs peuvent se servir. Et, contrairement aux politiques qui peuvent être réécrites ou aux déclarations de valeurs qui peuvent s’effacer, ces modèles d’actionnariat salarié ancrent la gouvernance partenariale dans la structure organisationnelle des entreprises, la rendant durable, culturelle et concrète au quotidien.

Pour Tim, il s’agit du cœur du sujet : « Si vous examinez les normes MGPP et vous vous demandez quelle forme d’actionnariat salarié les respecte toutes, la réponse sera : “aucune”. Cependant, prises ensemble, elles prouvent un fait plus global : nous pouvons structurer notre économie de manière à la mettre au service de la majorité. »

Une nouvelle façon de faire des affaires

Afin d’aider les dirigeant.e.s d’entreprises à adopter le statut de « benefit corporation » (société d’intérêt social) comme condition préalable à la certification B Corp, le B Lab États-Unis et Canada a créé cette ressource téléchargeable, le « Board Playbook » (guide du conseil d’administration) [en anglais], pour présenter le processus et démystifier les risques.

Les dimensions culturelles de l’actionnariat salarié

Les structures comme les coopératives, les plans d’actionnariat des salarié.e.s et les fiducies déterminent la manière dont la propriété est répartie. Toutefois, le domaine d’impact de la mission et de la gouvernance des parties prenantes nous rappelle que la gouvernance est autant une question de culture que de mécanismes. Les entreprises détenues par les employé.e.s les plus prospères ne s’arrêtent pas aux structures formelles. Elles créent des environnements au sein desquels la transparence, la responsabilisation et le respect sont des pratiques quotidiennes.

Comme Tim l’a expliqué, même dans les entreprises dotées de plans d’actionnariat des salarié.e.s, qui ont tendance à fonctionner avec une structure traditionnellement plus hiérarchique, la culture transforme la dynamique : « Il y a une forme de reconnaissance qu’un.e membre de la haute direction ne sait pas mieux commander une machine-outil que la personne qui l’opère. La question devient donc : comment la direction peut-elle soutenir les employé.e.s de manière à les aider à accomplir leurs tâches plus efficacement, à ressentir une plus grande satisfaction au travail et, au bout du compte, à créer une plus grande richesse pour leur retraite? »

Cet état d’esprit apparaît dans des pratiques telles que la gestion à livre ouvert. Par exemple, SRC Manufacturing est connue pour ses « caucus », des réunions qui rassemblent des petits groupes d’employé.e.s pour passer en revue les résultats financiers, comprendre les facteurs qui influencent les chiffres et déterminer des façons de s’améliorer. « Le but n’est pas d’attribuer le blâme », a précisé Tim. « C’est de se demander quel rôle on doit jouer pour améliorer les résultats. Comment mon équipe peut-elle contribuer? » Ces conversations transforment la littératie financière en responsabilité partagée, créant le type d’engagement requis par les normes MGPP.

D’autres sociétés adoptent des approches similaires en formant des comités culturels ou des groupes de travail interservices qui donnent aux employé.e.s voix au chapitre en ce qui concerne le fonctionnement quotidien de l’entreprise. Comme Tim l’a formulé : « Les meilleures entreprises ne se contentent pas de respecter les exigences de la loi. Elles vont au-delà pour prouver à leurs collaboratrices et à leurs collaborateurs qu’elles les écoutent et, si la réponse est non, elles en expliquent les raisons. Nous parlons de véritables boucles de rétroaction. La direction ferme la boucle et les employé.e.s peuvent comprendre comment leurs voix ont été prises en compte dans la décision. Cette démarche renforce la confiance. »

Pour Tim, ces exemples soulignent une vérité plus globale : l’équité et la faculté d’agir sont des éléments inhérents à l’actionnariat salarié. Les modèles d’actionnariat peuvent commencer par des cadres juridiques. Toutefois, ils se transforment seulement en structures concrètes lorsqu’ils sont associés à des pratiques qui donnent l’impression aux employé.e.s que leurs voix comptent.

S’engager dans la bonne voie

La mise en place de l’actionnariat salarié ne commence pas par la recherche du modèle idéal, mais de celui qui convient le mieux. Chacune des quatre options présentées comporte des structures de gouvernance, des implications culturelles et des coûts distincts. La question n’est pas tant de savoir quel est le meilleur modèle, mais plutôt quel est celui qui s’harmonise le mieux avec la taille, le secteur et les objectifs à long terme de l’entreprise.

Tim commence souvent par les bases. « Lorsque je rencontre une entreprise qui n’est pas détenue par ses employé.e.s, ma première étape consiste à comprendre sa nature et son identité. Quel est son profil? Qu’est-ce qui motive ses propriétaires? Ces personnes cherchent-elles à réaliser une vente rapide ou à créer un avantage durable pour leurs employé.e.s et leurs communautés? » Une fondatrice ou un fondateur partant à la retraite et souhaitant préserver les emplois pourrait pencher pour une fiducie, tandis qu’un plan d’actionnariat des salariés conviendrait parfaitement à une entreprise manufacturière de taille moyenne qui cherche à créer une sécurité pour la retraite de son personnel. En revanche, un plan d’actionnariat des salarié.e.s peut ne pas avoir de sens pour une petite librairie communautaire qui n’a pas les marges ni l’envergure nécessaires pour soutenir cette structure. Tandis qu’une coopérative de travail pourrait être parfaite dans ce contexte, cette structure ne conviendrait probablement pas à une entreprise de fabrication industrielle qui emploie 500 personnes.

C’est dans ce cadre que le travail de comparaison du NCEO prend toute son importance, car il permet d’exposer clairement les compromis entre les différents modèles d’actionnariat salarié [en anglais]. Chaque modèle a ses points forts : les coopératives mettent l’accent sur la voix du personnel, les plans d’actionnariat des salarié.e.s sur la richesse, les fiducies sur l’intendance et les régimes de participation directe sur la flexibilité. Cependant, la question n’est pas de les classer, mais de montrer qu’il existe toujours une avenue viable pour intégrer la gouvernance partenariale.

Au bout du compte, cela reflète le cadre dessiné par les normes MGPP du B Lab. Les normes ne prescrivent pas une forme unique de gouvernance. Elles fixent des attentes et laissent une marge de manœuvre aux entreprises pour leur permettre de choisir la structure qui convient à leur mission, leurs valeurs et leurs engagements envers leurs parties prenantes. Les modèles d’actionnariat salarié fonctionnent de la même manière. Ils n’imposent rien. Mais, ils fournissent de véritables moyens structurels pour intégrer la voix des parties prenantes et la responsabilisation dans les entreprises sur le long terme.

L’actionnariat comme avenue vers le partage de la prospérité

Pour Tim, le pouvoir de l’actionnariat salarié ne repose pas seulement dans ses structures, mais aussi dans ce qu’elles rendent possible : des communautés au sein desquelles les personnes se sentent en sécurité, respectées et investies dans l’avenir. « En fin de compte, l’actionnariat confère de la dignité aux personnes », a-t-il affirmé. « Il crée de la stabilité dans leur vie et une participation dans quelque chose de plus grand qu’elles. »

Il s’agit au bout du compte du but des normes. Ce ne sont pas seulement des politiques, mais des pratiques qui rendent la prospérité et la gouvernance tangibles pour les personnes qui font fonctionner les entreprises.

Apprenez-en davantage sur les normes mises à jour du B Lab pour la mission et la gouvernance des parties prenantes en consultant la page Web qui présente un aperçu du domaine d’impact MGPP [en anglais].

Copyright : B Lab États-Unis et Canada

Inscrivez-vous à notre newsletter B The Change

Lisez des histoires sur le mouvement B Corp et sur les personnes qui utilisent les entreprises comme une force pour le bien. La newsletter B The Change est envoyée chaque semaine le vendredi.