Embedding Stakeholder Governance Through Alternative Ownership: Insights from Tim Garbinsky and Natalie Reitman-White

December 3, 2025

Tim Garbinsky and Natalie Reitman-White arrive at employee and purpose-driven ownership models from different vantage points, but they illuminate the same underlying truth: ownership structure shapes how power, culture, and long-term purpose show up inside a company.

Tim first saw this as a young clerk in an employee-owned pharmacy in Madison, Wisconsin, where everyday interactions carried a profound sense of dignity and shared accountability. Natalie encountered it later through her work designing purpose trusts—a legal structure in which ownership is placed in a trust to protect a long-term mission or stakeholder purpose. (Because this is the structure Natalie implements in practice, it’s the one she speaks to most directly in the sections that follow.)

Both now operate at the intersection of ownership and governance: Tim as Communications Director at the National Center for Employee Ownership (NCEO), and Natalie as founder of Purpose Owned. Their perspectives show how expanding ownership beyond investors can create more durable pathways for stakeholder voice, shared prosperity, and mission protection.

These insights connect directly to B Lab’s Purpose & Stakeholder Governance (PSG) Impact Topic: building companies in which prosperity is shared, and stakeholder interests meaningfully shape decision-making. Employee ownership provides one set of pathways through worker cooperatives, employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs), employee ownership trusts (EOTs), and direct share programs. Purpose trusts offer another, embedding mission and stakeholder priorities directly into the ownership structure itself. Taken together, these models show that the most reliable way to uphold stakeholder commitments is to build them directly into a company’s ownership structure.

Impact Topic in Practice

The Purpose & Stakeholder Governance Impact Topic supports B Lab’s goals to overturn shareholder primacy, put sustainability at the right level within the company, and fight greenwashing. This guide helps companies put the standards into practice.

The Link Between PSG Standards and Employee Ownership

The Purpose & Stakeholder Governance standards were created to shift business away from shareholder primacy (the idea that a company exists only to maximize profit for its owners) and toward a model in which long-term purpose and accountability to all stakeholders guide decision-making. Rather than asking companies to sign on to lofty values, the standards set out a concrete governance framework that makes stakeholder voice part of how a company actually operates.

The six requirements cover the essentials of responsible governance:

- PSG1. Purpose: Every company must define a positive purpose that extends beyond financial returns and anchors its strategy

- PSG2. Stakeholder Input: Companies need clear processes to consider the perspectives of workers, customers, communities, and the environment in key decisions

- PSG3. Grievance Mechanisms: Stakeholders must have safe and accessible ways to raise concerns, and companies must take responsibility for addressing them

- PSG4. Responsible Communication: Companies are expected to be truthful and balanced in how they talk about their social and environmental impact

- PSG5. Oversight: Leadership must integrate purpose and stakeholder governance into board agendas and executive accountability

- PSG6. Transparency: Companies must regularly share their impact performance publicly, with stronger expectations for larger or more complex organizations

The framework adapts to context: a 15-person startup won’t be expected to meet the same governance bar as a global corporation. Smaller companies might fulfill the standards with simple feedback loops or a basic grievance process, while larger businesses are expected to demonstrate board-level oversight, executive accountability, and robust public reporting.

What makes the PSG standards distinctive is that they don’t prescribe a single way of governing. Instead, they open space for companies to choose structures that fit their size, culture, and sector while still ensuring that purpose and stakeholder accountability are non-negotiable.

Ownership structure is one of the clearest tools available for meeting that bar. Cooperatives, ESOPs, and direct share programs broaden who participates in value and, often, who participates in governance. Purpose trusts push the idea further by placing ownership in a trust with a legally defined mission or stakeholder benefit at its center. As Natalie notes, “ownership is a design question,” one that can be shaped so that purpose guides the company over time.

WinCo Foods, a Boise-based grocery chain, ranks near the top of NCEO’s “Employee Ownership 100” list.

Photo: Zoshua Colah

Forms of Employee Ownership (and How They Advance Stakeholder Governance)

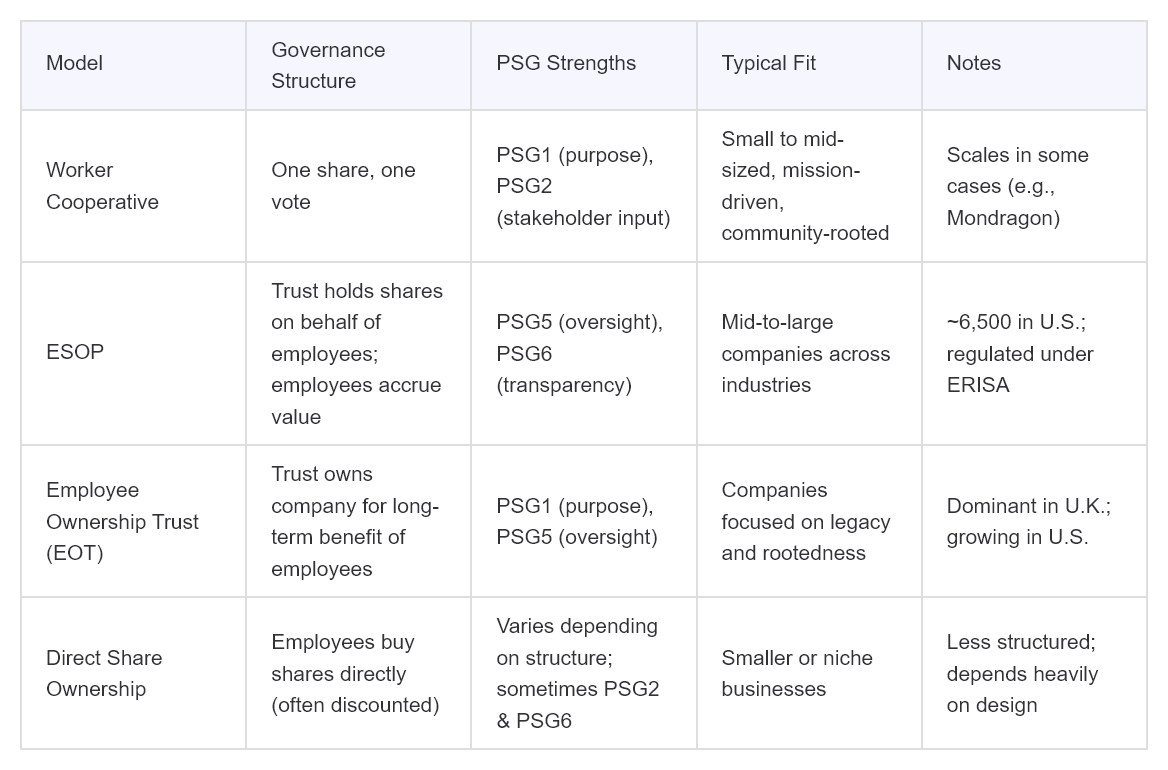

Employee ownership isn’t one-size-fits-all. As Tim puts it, “I think of employee ownership as a toolkit. Worker cooperatives, ESOPs, EOTs, direct share programs—each brings different strengths to the table. No single model is perfect, but across them you can usually find the right fit for almost any business.” While each model takes a different approach to distributing ownership and voice, what they all share is a capacity to move stakeholder governance from paper policies into lived culture.

Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs)

ESOPs are the most common form of employee ownership in the U.S., with around 6,500 companies structured this way. Instead of giving each employee a direct vote, ESOPs create a trust that holds company shares on behalf of workers. Shares are allocated to individual accounts, which grow in value over time as the business succeeds—and employees don’t pay for them out of pocket. “In my ten years, I’ve never met an employee who had to buy in personally,” Tim notes. “It’s truly a benefit earned through labor over time.”

That structure makes ESOPs powerful retirement vehicles. Tim recalls interviewing an electrical manufacturing worker who retired two years early because of his ESOP balance. “You hear stories of 45-year-old grocery clerks with million-dollar retirement accounts. In a country where pensions have disappeared and 401ks depend on employees contributing their own paychecks, ESOPs fill a gap. They make sure people don’t have to keep working into their eighties.”

From a governance perspective, ESOPs connect most directly to PSG5 (oversight) and PSG6 (transparency). Under ERISA law, the trustee is legally bound to act in the best interest of employee-owners, and that duty is enforceable by the Department of Labor, which can investigate violations, sue, and award settlements to employee participants. In practice, this means accountability is not only cultural, but legal. “In a conventional business, an owner might sell if the price feels right. In an ESOP, the trustee has to ask: is selling now truly in employees’ long-term interests?” Tim explains.

Transparency is also built into the structure. By law, ESOP companies must communicate plan details, annual share valuations, and other disclosures employees would never receive in a conventional company. Employees themselves often get to vote on big-picture issues like a potential sale, ensuring their voice is present at defining moments.

The strength of ESOPs lies not only in the wealth they build, but in the guardrails that hold companies accountable. ESOP companies generate more jobs, default less on loans, and are significantly more likely to survive economic downturns than their conventionally owned peers. Together, that makes them both a wealth-building tool and a resilient governance model.

Worker Cooperatives

Worker cooperatives are the oldest and most intuitive form of employee ownership. They follow the principle of “one share, one vote,” giving each worker equal voice in major decisions. For many people, this is the clearest expression of democratic governance.

In the U.S., co-ops are often associated with small, community-based businesses—groceries, cafés, bookstores—but Tim pushes back on the idea that they can’t scale: “One of the largest employee-owned companies in the world, Mondragon in Spain, is a federation of worker-owned businesses with tens of thousands—maybe close to a hundred thousand—people involved. That shows co-ops aren’t just mom-and-pop shops. They can be large, complex enterprises.”

NCEO’s research verifies more than 750 worker co-ops in the U.S., across industries from food service and health care to manufacturing, technology, and design. Structurally, each worker purchases a single share, which grants both ownership and a vote in electing the board of directors. That board oversees strategy and hires professional managers or delegates day-to-day operations, so governance remains democratic without becoming unwieldy.

Because co-ops embed worker and community benefit into their purpose, they resonate with PSG1 (purpose), which requires companies to define a positive mission beyond financial returns. They also connect most directly to PSG2 (stakeholder input). “The business has to look out for what the workers want, because they actually control it,” Tim explains. Day-to-day management is handled by elected boards or professional managers, but strategic direction rests with worker-owners. Tim is quick to add that co-ops aren’t chaotic: “People sometimes think, ‘Oh, everyone makes every decision,’ or ‘I can fire my coworker.’ That’s not how it works. Worker co-ops operate with rules and well-established best practices.”

Unlike ESOPs, co-op shares aren’t designed as retirement assets: workers may still have 401ks, but their share represents voice and accountability more than long-term wealth.

Employee Ownership Trusts (EOTs)

EOTs are relatively new in the U.S. but are the dominant form of employee ownership in the U.K. In this model, the business is owned by a trust that is legally obligated to benefit employees. Unlike co-ops or ESOPs, shares aren’t allocated individually; instead, the trust itself owns the business, and employees typically benefit through profit-sharing and retirement plans.

EOTs differ from purpose trusts, which can be designed to benefit a broader mix of stakeholders such as employees, communities, customers, farmers, or the environment. EOTs, by contrast, are specifically structured to benefit employees as the primary stakeholder group.

Because the trust’s governing documents can be written with employee wellbeing at the center, EOTs often have the strongest tie to PSG1 (purpose) and PSG5 (oversight). “The idea is that if you want to say no to a sale, you can,” Tim explains. “The trust can decide to keep the company rooted in the community and jobs in place, because the purpose isn’t just maximizing shareholder value; it’s looking out for employees.”

EOTs don’t fall under ERISA like ESOPs, which means they lack the same regulatory framework but also avoid some of the rigidity. That flexibility makes them attractive to smaller companies seeking affordable ways to embed stakeholder priorities in governance. While there are only around 60 EOTs in the U.S. today, their popularity is growing as more founders look for succession plans that enshrine long-term stewardship rather than short-term exit value.

Direct Share Ownership

The simplest model is direct share ownership, in which employees buy stock directly—sometimes at a discount or over time. This approach is highly flexible: some companies combine it with profit-sharing pools or match employee purchases with stock grants. In some cases, sellers make ownership possible by offering lower prices, seller-financed loans, or allowing employees to use bonuses to buy shares.

Because it relies on employees’ ability and willingness to invest, direct ownership often works best in smaller firms or as part of a gradual succession plan. It can also take the form of equity compensation—such as stock options, purchase plans, or restricted stock—which rarely transfer majority ownership but can build engagement and reward tenure.

Direct ownership can advance PSG2 (stakeholder voice) and PSG6 (transparency), but its effectiveness depends heavily on how widely shares are distributed and whether governance rights are attached. Without those elements, it risks becoming symbolic rather than structural.

As Tim emphasizes, no single model fulfills every PSG requirement on its own. Worker co-ops excel in democratic governance, ESOPs in wealth-building and accountability, EOTs in purpose and stewardship, and direct share programs in flexibility. “There isn’t a silver bullet,” he explains. “But each model fulfills at least some of the standards, and often several, in significant ways.”

The result is a rich toolkit of employee-ownership pathways that companies can draw from. And when paired with alternative structures like purpose trusts, which embed mission or stakeholder priorities directly into ownership, these models help move stakeholder governance from aspiration to durable design.

For Tim, that’s the heart of it: “If you looked at the PSG standards and asked which form of employee ownership fulfills them all, the answer is none. But together they prove a larger point: we can structure our economy to work for the majority.”

A New Way of Doing Business

To help business leaders navigate the journey to adopt benefit corporation status as a requirement of B Corp Certification, B Lab U.S. & Canada provides this downloadable resource, the Board Playbook, to lay out the process and demystify the risks.

Purpose Trusts as a Distinct Governance Pathway

Natalie approaches ownership as a design challenge: if you want a company to serve a mission or a group of stakeholders, you can hard-code that intention into who owns the business. Purpose trusts are the tool she helps companies use to do that. Rather than distributing shares to employees, a purpose trust becomes the permanent owner and legally requires the board to run the company in service of the trust’s stated purpose.

This model is flexible enough to serve very different aims. Patagonia placed its voting stock into a trust designed to “benefit the planet.” Other companies use the structure to center employees. Natalie describes a landscaping company transitioning into a purpose trust that requires the board to maintain independence, treat employees well, and share profits broadly. “Employees don’t have to buy in or hold stock, which is especially important in sectors with high turnover or varied immigration statuses,” she notes. She’s also worked with companies whose purposes are more specialized—such as advancing science literacy—which illustrates how adaptable the design can be.

Some companies include employee seats on the trust’s stewardship committee, giving workers a formal role in oversight. As Natalie explains, “the trust’s stewards monitor things like turnover, employee surveys, and working conditions. If they see deterioration, they hold the board accountable for failing to uphold the purpose.” Purpose trusts can also be designed for multiple stakeholder groups. At Organically Grown, for example, the trust balances the interests of farmers, customers, employees, investors with non-voting stock, and a community advocacy organization—each contributing something essential to the enterprise.

Companies often choose this structure because it aligns ownership with values and protects mission continuity. Natural Investments, for instance, transitioned into a purpose trust to ensure governance and financial benefit matched its commitments to social justice and environmental responsibility. “We’re putting our structure where our mouth is,” the firm told Natalie. Purpose trusts also eliminate the fear of a values-driven company being sold or moved off mission. “You can say, ‘Our company isn’t for sale; it’s owned by and for its purpose,’” Natalie says. “That gives employees a sense of long-term security.”

Setting up a purpose trust requires legal design work—often starting around $15,000—and, in some cases, financing a buyout so that shares can move into the trust. But many companies need no outside investors: the trust owns the company outright, and the business reinvests what it needs while distributing excess profits according to the trust purpose. To support wider adoption, Natalie has helped establish the Purpose Trust Ownership Network, which provides open-source resources and examples of companies using the structure.

From a PSG perspective, purpose trusts most directly support PSG1 (purpose), PSG2 (stakeholder input), and PSG5 (oversight). The trust’s purpose functions as a structural mission lock, stewardship committees create built-in channels for stakeholder voice, and the board is legally required to uphold the trust’s purpose over time. For companies seeking a durable way to protect mission and embed stakeholder governance, purpose trusts offer one of the most structurally secure pathways available.

How Ownership and Governance Structures Shape Culture

Ownership and governance design shape culture as much as they determine formal authority. Structures like ESOPs, cooperatives, and purpose trusts create the conditions for transparency, accountability, and shared voice; but culture is what brings those conditions to life.

Tim sees this clearly, even in ESOP companies that retain conventional hierarchies. “There’s recognition that a C-suite executive doesn’t know how to run a lathing machine better than the operator does,” he says. “So the question becomes: how can leadership support employees to do their jobs more effectively, enjoy them more, and ultimately build retirement value?” When ownership is shared, respect and role clarity become cultural norms rather than aspirational values.

Natalie sees a parallel in purpose-trust-owned companies, where structural accountability becomes a cultural expectation. As she explains, “A benefit corporation can still be owned by two people who ultimately take all the money and make all the decisions. But with a purpose trust, no individual owns the company. The purpose owns the company. That adds another layer of accountability.” It also shapes how employees understand their role and what they can expect from leadership. One worker put it plainly after the transition to a purpose trust: “A lot of people say you’re working for the mission when you’re really working for the man. Now we’re actually owned by the mission. This makes it real.”

What Tim and Natalie describe isn’t culture in the abstract; it’s culture shaped by what ownership makes possible. ESOP trustees bound by ERISA create one form of accountability; purpose-trust stewards enforcing mission create another. Real culture change happens when those structures are paired with practices—open-book management, listening sessions, shared financial literacy, and meaningful feedback loops—that make accountability felt day to day.

Choosing the Right Path

Every ownership model comes with strengths, limits, and cultural implications. The work is not to identify a perfect structure, but to understand which option aligns with a company’s goals, constraints, and stakeholder commitments.

Tim tends to start with practical fundamentals. “When I sit down with a company that isn’t yet employee-owned, my first step is to understand who they are,” he says. “What motivates the owner? Are they seeking a quick sale, or are they looking to create a lasting benefit for employees and the community?” A retiring founder committed to preserving jobs might lean toward an EOT; a mid-sized manufacturer aiming to build retirement security could be a strong fit for an ESOP. A worker co-op might thrive in a small community bookstore, but likely wouldn’t suit a 500-person industrial manufacturer with complex operational structures.

Natalie approaches the conversation by surfacing the foundational questions that must be answered long before any legal drafting. “Ownership is ultimately a set of design choices,” she explains. “You ask: What is the purpose the company should serve? Who should hold the steering wheel in the stewardship group? How should profits flow? And what’s the best way to transition existing shares into the new structure? You don’t want to run up legal hours before those decisions are clear.”

Once those questions are on the table, patterns emerge—particularly around what a company is actually trying to protect or advance. That clarity often reveals why purpose trusts appeal to a wide range of companies. “The common thread is motivation,” Natalie adds. “If the primary goal is to maximize investor returns and sell for the highest price, the conventional corporate model already exists for that. A purpose trust makes sense when you want a for-profit business that inherently aims to create pro-social benefits alongside profit.” It’s especially powerful when founders want their mission to outlive them or want employees or other stakeholders to share in governance and benefit without requiring them to buy in.

Purpose trusts also change who carries the financial burden. Workers never need to purchase stock, vest, or hold equity. But founders may still need to be bought out, and legal design work is unavoidable. “Many founders can’t simply give the company away,” Natalie notes. “You might need a loan so the shares can move into the trust, and then have the company pay down that loan over time.”

Across all models, decision-makers are navigating genuine tradeoffs. Co-ops foreground democratic governance. ESOPs build wealth and provide strong legal oversight. EOTs offer stewardship and stability. Direct share programs provide flexibility. Purpose trusts embed mission and multi-stakeholder governance. The point isn’t to rank them; it’s to show that companies have meaningful, structurally different pathways to embed stakeholder governance in durable ways.

Ownership Model Comparison

That is also the spirit of the PSG standards. They don’t prescribe a single governance model; they set expectations and leave room for companies to choose structures that fit their purpose, values, and stakeholder commitments. Ownership structures are among the clearest ways to meet those expectations in practice.

Ownership as a Path to Shared Prosperity

The produce section at an Orlando, Florida location for Publix Supermarkets, the largest employee-owned corporation in the U.S.

For Tim, the promise of employee ownership lies not only in the structure but in what it unlocks for people. “At the end of the day, ownership gives people dignity,” he says. “It creates stability in their lives and a stake in something larger than themselves.” That stability shows up in retirement accounts, job security, and the sense that hard work builds something lasting.

Natalie sees a parallel outcome in purpose-trust-owned companies, where mission and stakeholder benefit are structurally guaranteed. “So many companies say they’re owned by their mission,” she notes. “A purpose trust is how you actually do it.” For founders, it ensures that values won’t be diluted by future ownership changes. For employees and other stakeholders, it provides clarity: the company can’t be sold out from under them, and the governing purpose is enforceable. As one Organically Grown employee put it, “if I work hard, I share in the returns. None of us can sell the company or take it off track from promoting organic agriculture. This makes it real.”

Their perspectives converge on a simple point: ownership choices determine whether stakeholder governance lives on paper or in practice. That is ultimately what the PSG standards call for: not just policies, but the structural commitments that make accountability, purpose, and shared prosperity real.

Learn more about B Lab’s updated Purpose & Stakeholder Governance Standard by visiting our PSG Impact Topic overview page.

Copyright B Lab U.S. & Canada

Sign Up for our B The Change Newsletter

Read stories on the B Corp Movement and people using business as a force for good. The B The Change Newsletter is sent weekly.